As happened in both California and Washington state referendums in recent years, what seemed like an easy path to victory for supporters of a mandatory GMO labeling law in Oregon has turned into a dog fight as the voting nears, while voters in Colorado appear poised to soundly reject the measure.

An Oregonian poll earlier this week showed Measure 92 behind by six points, trailing 48-42. A poll released in July by Oregon Public Broadcasting put support for GMO labeling at 77 percent.

The sharp drop-off mirrors what happened in California and Washington, where the labeling forces held would seemed like insurmountable leads until the last month or two of the campaign.

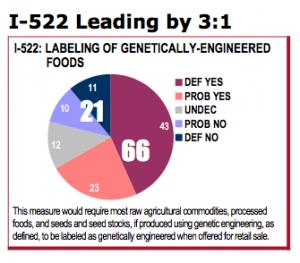

California voters narrowly turned down labeling in 2012. Washington voters rejected a similar measure, I-522, in 2013. Both lost by nearly identical 51-49 margins after leading by 3-1 or more.

What’s behind the pattern of erosion of support as the campaign wears on. Cary Gillam, a Reuters agriculture correspondent known for her anti-GMO bias, claims it’s all about money and advertising by Big Ag.

But as was the case in the two other western states that voted on labeling bills, the more voters learned about the law and the science behind genetically modified crops and foods, the more support eroded.

“Fresh polling showed support for the Oregon GMO labeling law waning in the face of a well-funded onslaught of advertising from labeling opponents,” she wrote. “In both states, the bid for votes on Nov. 4 is largely coming down to the size of each side’s bank account.”

Gilliam then gives the platform to one of the leader’s of the ‘yes on 92′ campaign, who are attempting to massage the news in case the worst happens from their perspective.

“We’re not able to compete with these massive contributions,’ Reuters quotes Larry Cooper, campaign chair for Right to Know Colorado. “I have not written off the campaign. But it is very much a David and Goliath situation.”

In fact, experts in polling and political behavior, backed by numerous studies have shown that the Gillam-anti-GMO theory–money is buys votes on controversial and complicated policy measures–is almost certainly wrong.

Grist’s Nathanael Johnson looked into what may be behind the yes vote collapse pattern after the Washington vote last year. “The Washington vote seems to be telling us that concern about GM food is broad and shallow,” he wrote. “That is, lots of people are vaguely worried about transgenics, but it’s not a core issue that drives majorities to the polls.”

“This was a solution looking for a problem,” he quoted Stuart Elway, president of the Seattle-based polling company Elway Research. “People were not highly agitated about GMO labeling.”

The key, Elway noted, was not the expenditure of money; it was that when people learned about the details of the measure, they came to see it as fraught with problems and unintended consequences.

Wrote Johnson: “While it’s nearly impossible for advertising to shift core values — like getting a lifelong Democrat to vote Republican or vice versa — it is possible for advertising to change the mind of someone who hasn’t fully committed. When people haven’t encountered the arguments on each side, those arguments tend to work.”

Chris Mooney, now writing for the Washington Post, picked up on that theme this week.

[W]hen people tell pollsters they favor GMO labeling, they don’t really know what they’re saying. Because overall public knowledge about GMOs is very low, many GMO polls give “a measure of what people will say they want to label when they have no idea what that means,” explains Yale public opinion researcher Dan Kahan.

In other words, because Americans don’t actually know a lot about genetically modified foods, polls that claim to show overwhelming support for labeling are probably not very reliable. Consider that a push poll conducted by the New York Times found that 93 percent of Americans favor labeling GM food. That’s almost certainly because poll questioners asked people whether they supported GMO labeling. But when not fed the possible answer–when poll takers were asked whether there was any additional information they would like to see on food labels–only 7 percent volunteered they supported labeling.

This is yet another piece of evidence suggesting that public opinion polls purporting to represent overwhelming support for GMO labeling our flat out wrong, despite the propaganda generated by anti-GMO advocacy groups. General polls don’t reflect how people really think about the issue of genetically modified foods or labeling–when they think about it all.

*****

Jon Entine, executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, is a Senior Fellow at the World Food Center, Institute for Food and Agricultural Literacy, University of California-Davis. Follow @JonEntine on Twitter

Comments